The reintroduction of the Eurasian beaver is a topic much debated across Europe and the UK, given its effects as an ecosystem engineer in rivers and streams. The species, which used to be widespread across England, Scotland and Wales, became extinct in the 16th century after widespread hunting (Countryfile, 2018). However, in recent years it has been suggested by academics and conservationists alike that the influence of beavers on water systems could be vital in restoring degraded wetland ecosystems.

Firstly, a quick introduction on the species. Beavers are best known for their long teeth and their construction of dams in streams and rivers, made by coppicing trees such as hazel and willow. The last wild beaver was killed in Britain some time in the 16th century, with its European cousins last spotted around the 18th century – beavers were prized for their fur and meat, but also for their castoreum, a substance which they used to scent mark their territory, which humans then collected for perfume (!) (RSPB). In 2016, beavers were given native status in Scotland, allowing those individuals which had already been released (legally or illegally) to spread (The Guardian, 2016). This news has received a mixed reception; many believe that it is beneficial to rewild a species which was once native to the area, but others fear a risk to fisheries – with dams potentially preventing the migration of commercially important fish such as trout and salmon (Countryfile, 2018).

The impacts of beavers on rivers and streams, and particularly their dams, are relatively well-studied. Beavers can build dams over 1m high, using stripped and coppiced vegetation to do so. They do this to create deep pools of water, which can be used as refuges (beavers prefer to move in water rather than on land), and to refrigerate food stores (Countryfile, 2018).

“The most significant geomorphic impact of beavers results from their dam building ability and the consequent impoundment of large volumes of water and potentially associated sediment and nutrient accumulation in ponds” – Puttock et al., 2018

The act of coppicing (or cutting down) trees to build these dams has a multitude of ecological benefits. Beaver coppicing has been shown to allow light to permeate through the woodland easier, and increase the availability of soil nutrients (Rosell et al., 2005). It can also reverse riparian (riverside) vegetation succession, creating an environment suitable for early successional species (Rosell et al., 2005), which affects levels of in-stream vegetation and therefore algal and macroinvertebrate assemblages. Changing the vegetation density of the riparian zone can also enhance waterfowl nesting cover adjacent to ponds (Rosell et al., 2005).

Beaver dams

According to a literature review by Kemp et al. (2012), “the most frequently cited benefits of beaver dams (are) increased habitat heterogeneity, rearing and overwintering habitat and invertebrate production”. An example of how this works, is illustrated by Rosell et al. (2005) – the woody debris which beavers collect for dam building can lead to much greater habitat heterogeneity (that is, variability in habitat types), which then leads to the creation of a greater number of ecological niches to be filled by multiple macroinvertebrate species. The scale of beaver activity can also change the morphology of a water course, forming deep pools behind dams, and altering water flow. But the benefits of dams can also be felt by mammals – the meadows which beavers can create through changing vegetation are reportedly used by white-tailed deer, moose and bears across North America, and beaver ponds offer improved hunting ground for bat species (Rosell et al., 2005).

In terms of landscape improvements, a 2018 study found that beaver ponds, which accumulate sediment through the slowing of water flow, may help mitigate the effects of agricultural soil erosion (Puttock et al., 2018). The damming and subsequent flooding of stretches of river has also been suggested to improve connectivity of flood plains and mitigate large floods. Dams can even help regulate nutrient levels – Puttock et al., (2018) recorded a reduction in downstream concentrations and loads of nitrogen, phosphate and suspended sediment during storm flows.

“Beavers, being ecosystem engineers, are among the few species besides humans that can significantly change the geomorphology, and consequently the hydrological characteristics and biotic properties of the landscape” – Rosell et al. (2005)

Reintroduction risks

Despite the potential benefits that reintroducing beavers to our waters might bring, many people remain sceptical at best, or afraid at worst. This fear is founded on three main concerns: firstly, that their dams impede fish migration and will subsequently destroy commercial and recreational angling, secondly that they carry the lethal tapeworm Echinococcus multilocaris (which can spread to dogs and people) or other diseases, and thirdly that beaver dams will lead to flooding.

The impacts of dams on the migration of fish have been intensively studied (Kemp et al., 2012). Beaver dams are an obvious barrier in a stream which can alter fish movement. However, it has been found that this only significantly effects fish under low water flow conditions – fish were seen congregating behind dams under abnormally low flow conditions in Nova Scotia, Canada, but there was no recorded effect under average or above-average flow (Kemp et al., 2012). As well as this, beavers rarely construct dams on large rivers, so do not significantly prevent fish migration in these instances. The effect of these dams on amphibians has also been studied: Rosell et al. (2005) found no significant difference in species richness or abundance between dammed and un-dammed streams, and in fact found some species only on rivers with large beaver dams. The extent to which fish passage will be blocked by beavers therefore depends greatly on water flow regime, as well as the size of the river and of the dam – but with these considerations, it is still unlikely that fish passage will be significantly negatively affected.

According to a 2017 news story published by The Telegraph, members of the National Union of Farmers Scotland have argued against the reintroduction of beavers, on the grounds that they spread disease and can negatively affect other species. These diseases include the aforementioned tapeworm, but also the parasite Giardia lamblia, a parasite which can live in many mammals (including humans). However, there is a very low incidence of Giardia in Norway (where large populations of beavers currently reside), meaning there is a low risk of spread by beavers, according to the Scottish Wildlife Trust.

But do beavers cause flooding? According to many studies, the presence of beavers and their wily water-redirecting ways can allow up to 40x the amount of water to be stored on a wetland (BBC, 2014) compared to a beaver-free area. They can also keep water in upland regions, meaning that water is more gradually released, causing less damage downstream. Beavers can help prevent flooding by decreasing peak discharge and stream velocity (Rosell et al., 2005). The creation of meandering rivers also reduces flow, and has the side effect of cleaning spawning gravels for fish (Countryfile, 2018).

Summary

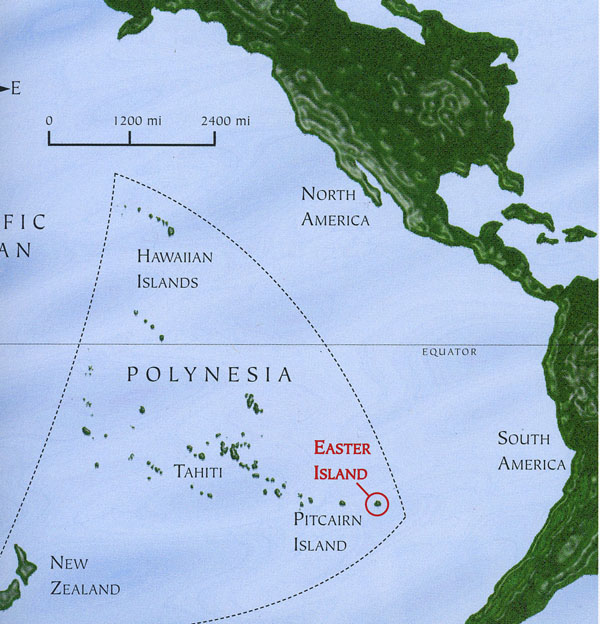

Are we likely to see beavers in the wild in the near future? European legislation (the EU Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC) requires that habitats should be assessed for the reintroduction of species including the Eurasian beaver to their once native ranges. Some reintroductions have already taken place around the UK. For example, the River Otter in Devon is now home to a population of around 30 beavers, though nobody quite knows how they got there (Crowley et al., 2017). In 2015, this beaver population became a “trial population” – government plans to remove them were rebutted by the county’s Wildlife Trust, allowing them to remain there unharmed.

In 2009, Britain’s first official (legal) beaver trial was initiated in Knapdale Forest, Scotland. A huge step forward for pro-rewilders, the trial has been extensively monitored and managed by the Scottish Wildlife Trust and its partners to ensure all beavers released are healthy, disease-free and can go on to further increase the local population. In order for beaver reintroductions to become more frequent, it is imperative that the public supports them – the fate of these charismatic animals in the UK therefore depends on public opinion and cooperation with the wildlife organisations responsible for the management of these trials.

“Maintaining positive public opinion is an essential component of long-term success of any reintroduction program” – Kemp et al., 2012

References

Countryfile (2018) Guide to Britain’s beavers: history, reintroduction and best places to see. [online] Available at: https://www.countryfile.com/news/guide-to-britains-beavers-their-history-reintroduction-and-where-to-see/ (accessed: 20/07/2019)

Crowley, S.L., Hinchliffe, S. & McDonald, R.A. (2017) Nonhuman citizens on trial: The ecological politics of a beaver reintroduction. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(8), pp.1846-1866

Kemp, P.S., Worthington, T.A., Langford, T.E., Tree, A.R. & Gaywood, M.J. (2012) Qualitative and quantitative effects of reintroduced beavers on stream fish. Fish and Fisheries, 13(2), pp.158-181

Puttock, A., Graham, H.A., Carless, D. & Brazier, R.E. (2018) Sediment and nutrient storage in a beaver engineered wetland. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 43(11), pp.2358-2370

Rosell, F., Bozser, O., Collen, P. & Parker, H. (2005) Ecological impact of beavers Castor fiber and Castor canadensis and their ability to modify ecosystems. Mammal review, 35(3‐4), pp.248-276

RSPB (n.d.) Beaver reintroduction in the UK. [online] Available at: https://www.rspb.org.uk/our-work/our-positions-and-casework/our-positions/species/beaver-reintroduction-in-the-uk/ (Accessed: 20/07/2019)

Scottish Wildlife Trust (n.d.) FAQ: Do beavers transmit disease? [online] Available at: https://www.scottishbeavers.org.uk/beaver-facts/beaver-trial-faqs/do-beavers-transmit-disease/ (Accessed: 20/07/2019)

The Guardian (2016) Beavers given native species status after reintroduction in Scotland. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/nov/24/beavers-native-protected-species-status-reintroduction-scotland (Accessed: 20/07/2019)

The Telegraph (2017) Beavers are back and thriving but not everyone is happy. [online] Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/01/22/beavers-back-thriving-not-everyone-happy/ (Accessed 20/07/2019)

BBC (2014) Who, What, Why: Do beavers prevent flooding? [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-magazine-monitor-26122318 (Accessed: 20/07/2019)