Indigenous communities tend to be best connected to the natural world. They have played a relatively tiny part in emitting anthropogenic greenhouse gases in comparison with Western societies like US and Europe (Green & Raygorodetsky, 2010). Yet the impacts of climate change fall disproportionately on Native people, like those living in the Arctic, in areas prone to extreme wildfires, and those living on Pacific Islands (Tsosie, 2007).

“Anthropogenic climate change is perhaps the ultimate manifestation of humans’ growing disconnect with the natural world, although not all societies share the same burden of responsibility for its creation” – Green & Raygorodetsky (2010)

There are several socio-political and environmental reasons why indigenous people are more vulnerable to climate change than someone perhaps born in the UK. One of the most obvious of these is the connection between native communities and their land and resources, as sources of employment, culture and heritage (Mihlar, 2008; Green & Raygorodetsky, 2010). Indigenous peoples often live in vulnerable environments: small islands in the Pacific which are already experiencing rising sea levels, and an Arctic environment which is rapidly melting, being just two examples (Mihlar, 2008). Because of this closeness to nature, these communities are often heavily reliant on their surroundings, and are the first to see environmental changes as a result of climate change. And these changes are already a life-threatening reality for many, with reports of people falling through thinning ice or going hungry where livestock and crops are failing (Mihlar, 2008). With the limited social and financial support that they have at their disposal, indigenous communities have a far greater vulnerability to environmental damage.

“More column inches have been devoted to the plight of the polar bear, than to the Inuit, the Arctic people who live in harmony with the wilderness.” – Mihlar (2008)

This second reason for increased environmental vulnerability stems from a legacy of discrimination and stereotyping of minority ethnic groups, and their exclusion from policymaking and the rights to their own land (Mihlar, 2008; Green & Raygorodetsky, 2010). In their review of environmental justice for indigenous people, Tsosie (2007) found that claims for justice centred on the need for regulatory control of their own land, and the right to be represented in decision-making processes which will affect their livelihoods. Native people know their land, how it is changing and what to do about it: their exclusion from policy-making and particularly from the right of self-determination*, is a serious problem. As well as this, their land is often earmarked for unfavourable projects, such as the uranium mines on Indian reserves in the US, which led to radioactive contamination of the land and water (Tsosie, 2007). The combination of such refusal of rights and disregard for the health and safety of native communities has combined to further their vulnerability to climate change – they are not considered in decision-making, nor are they financially supported or prioritised in policy by the wider government.

*self – determination: The right for a group of people to manage their own affairs and land without external interruption. The right to sovereign power over the land of your ancestors and family.

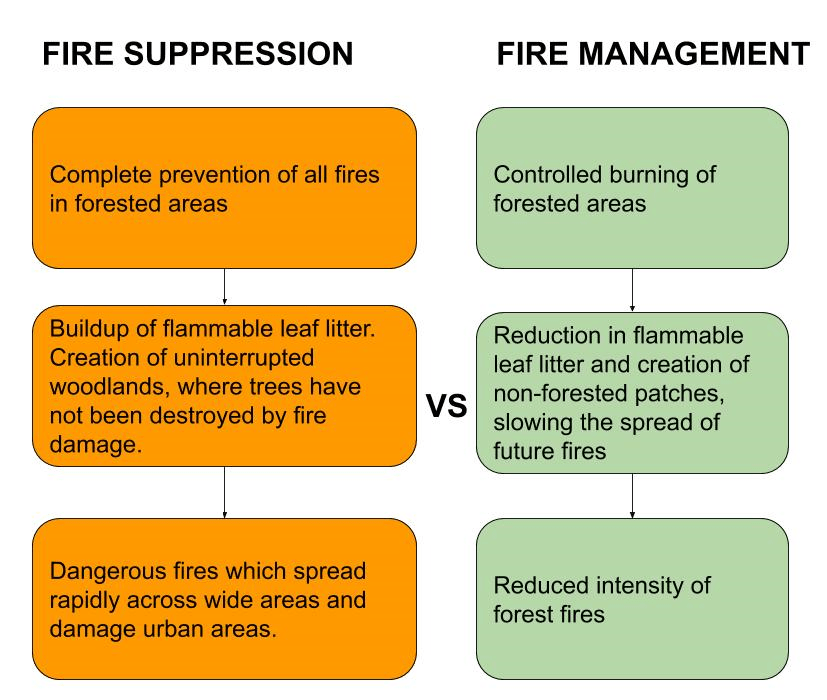

When indigenous people are granted the rights to manage their own land and included in policy, projects are guided by indigenous knowledge and are often made safer, both for humans and for the wider environment. Inclusion would encourage the sharing of unique indigenous knowledge, which would dramatically increase both Western understanding of environmental change, but also promote the rights of native people and raise awareness of the challenges they face. For example, when Aboriginal communities in Australia (rather than external business) managed local ecotourism projects themselves, they promoted conservation and shared their cultural understanding of the region with others, whilst also boosting employment and the local economy (Zeppel, 2003). As well as this, the different ways of thinking and generations of traditional understanding presented by the Miriwoong people of Australia bolstered scientific recordings of weather events, seasonality and fire regime in their area (Leonard et al., 2013). And a lot can be learned from sub-Saharan indigenous communities, whose practices of fallow cultivation to encourage forest growth, carbon conservation within soils through zero-tillage, and pest control with the use of intercropping and pest-resistant seed varieties, could provide alternative and useful knowledge with regards the sustainability of agriculture (Ajani et al., 2013). Indigenous people have the right to be heard and protected by wider society. And as a society, we must look to protect our most vulnerable members, and cherish their unique understanding of the ways in which the environment responds to change.

“The freedom to govern ourselves, leverage our traditional knowledge, and adapt to our changing circumstances is essential to realizing a more sustainable and climate-resilient future —particularly through the leadership of indigenous and community women.” – The Indigenous and Community response to the IPCC report “Special Report on Climate Change and Land from Indigenous Peoples and local communities”.

References

Ajani, E.N., Mgbenka, R.N. & Okeke, M.N. (2013) Use of indigenous knowledge as a strategy for climate change adaptation among farmers in sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for policy. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, pp.23-40

Green, D. & Raygorodetsky, G. (2010) Indigenous knowledge of a changing climate. Climatic Change, 100(2), pp.239-242

Leonard, S., Parsons, M., Olawsky, K. & Kofod, F. (2013) The role of culture and traditional knowledge in climate change adaptation: Insights from East Kimberley, Australia. Global Environmental Change, 23(3), pp.623-632

Mihlar, F. (2008) Voices that must be heard: minorities and indigenous people combating climate change. Minority Rights Group International: London.

Rights and Resources Initiative (2019) IPCC agrees with indigenous peoples and local communities on climate change. [online] Available at: https://ipccresponse.org/our-response (Accessed: 22/07/2020)

Tsosie, R. (2007) Indigenous people and environmental justice: the impact of climate change. U. Colo. L. Rev., 78, p.1625

Zeppel, H. (2003) Sharing the country: Ecotourism policy and indigenous peoples in Australia. Ecotourism policy and planning, pp.55-76